Have some Bristol primary schools been ‘forced’ to become academies?

Have some Bristol primary schools been ‘forced’ to become academies?

Repair-Ed Engagement Fellow, Fatima Mohamed Ali, writes about academisation in Bristol Schools

16 August 2024

What are academies?

Academies are state-funded schools which are independent from local authorities. Unlike other state-funded schools, academies are not overseen by local councils, giving them more autonomy in how the school is run. Controversially, they also have the power to decide how to spend their money. Legally, academies are run by ‘trusts’, which can be a multi academy trusts (MAT) – running several schools – or a single academy trust (SAT) which runs just one school. The government maintains that MATs are networks of schools which work to support each other and raise standards (Department for Education, 2023).

Why do academies exist?

It is widely held that the academies programme is part of the wider political agenda of privatising our national services. Tellingly, it was announced in the Schools Bill (2022) that all existing and new schools will become academies by 2030. Although there is an emphasis on school autonomy, parental ‘choice’, improvement driven by competition and philanthropic interventions, Kirsty Morrin (2020) maintains that these neo-liberal reforms are “…underpinned by the political discourse that these changes are for the ‘public good’ and are necessary and equitable.” (p.1). The emphasis on philanthropy is particularly disturbing given there are MAT schools in Bristol linked to The Society of Merchant Venturers whose money was made from the trafficking and trading of enslaved African people (Steeds and Ball, 2020).

Although academy schools cannot be run for direct profit, conflicts of interest remain within the financial management of academies and money can be made through the contracting of school services (Panorama, 2018). There are also widely reported disparities in pay with the highest-earning academy chief’s annual salary nearing half a million pounds (Schools Week, 2024). Most disturbingly, there is eventual transfer of land by local authorities to academy sponsors of the land a school stands on (Department for Education, 2022). These questions surrounding ownership of land, spending of public funding and inflated pay of Chief Operating Officers, give rise to concerns about the back-door privatisation of our education system (Mansell, 2017).

How many academy schools are there in Bristol?

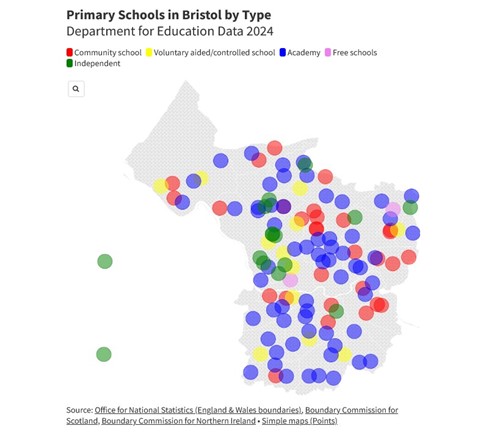

In the map below, Bristol primary schools are broken down by ‘type’. Of approximately 105 primary schools in the city, 65 are currently academy schools (62%). There remain only 25 community (Local Authority) primary schools in the city (24%).

This interactive map shows the locations of Bristol primary schools by governance type, drawing on Department for Education 2024 data.

What is ‘forced’ academisation?

Depending on circumstances, a school can become an academy through ‘academy conversion’ or ‘academy sponsorship’. These different models of academisation happen for different reasons and lead to quite different outcomes. Though schools can voluntarily become academies – many schools convert because their governing boards are put under pressure by the Regional Schools Commissioner or the diocese, or because they feel they must ‘jump before they are pushed’ (NEU, 2024; Dewes, 2024).

When a school is judged as ‘inadequate’ by Ofsted, it can be compelled to become an academy (Education Committee, 2024). For schools in this position, the Secretary of State for Education sends the school something called an ‘academy order’, which starts the process of an existing MAT being chosen and paid by the Department for Education to sponsor the ‘inadequate’ school to become part of that academy trust (Education Committee, 2024). This process is often referred to as ‘forced academisation’ (Education Committee, 2024). The government maintains that joining a MAT is expected to improve the ‘failing’ school’s performance (Education Committee, 2024).

However, the policy of compulsory academy orders following ‘inadequate’ judgements has been heavily criticised (NEU, 2024; Education Committee, 2024). Concerns have been raised about the high-stakes nature of Ofsted’s inspections and the stress and anxiety experienced by school staff due to this policy (NEU, 2024; Education Committee, 2024). The Education Committee has recommended that the Department for Education should assess its policy of maintained (council-run) schools which are ‘forced’ to become academies (Education Committee, 2024).

Which Bristol schools have been ‘forced’ to academise?

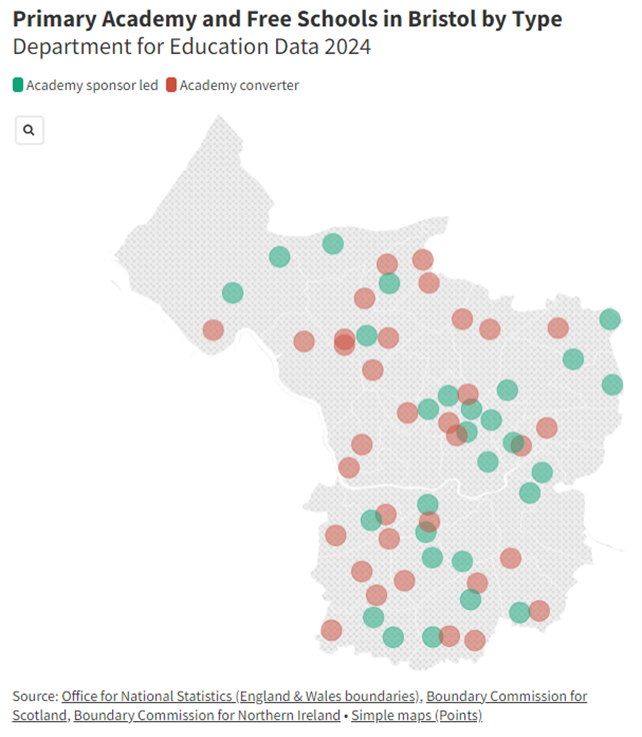

The map below shows that 34 primary schools in Bristol voluntarily converted to become academies whereas 28 local primary schools were ‘forced’ to academise.

Once a school is academised, the MAT is responsible not only for its finances but also its academic performance. For schools graded as ‘inadequate’ by Ofsted and forced into academisation, a large proportion of sponsorship intervention is focused on increasing the academic performance of pupils. However, research has shown that academisation does not necessarily improve the academic outcomes of a school and ‘do not provide an automatic solution to school improvement’ (Education Policy Institute, 2017, p.3). Furthermore, evidence has shown that local authority run schools perform better than MATs (TES, 2023).

Is ‘forced’ academisation more common in areas of Bristol with higher levels of economic disadvantage?

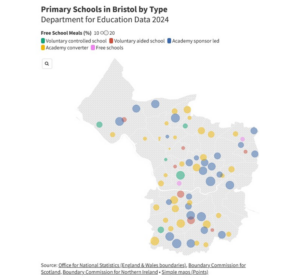

In this map, the colour of the circles represents the school type. The size of the circles represents the percentage of pupils in receipt of Free Schools Meals.

If FSM-eligibility is accepted as a proxy indicator for economic disadvantage, this map indicates that academy sponsor-led schools are occurring more in areas of Bristol with higher levels of economic disadvantage.

Why does this matter?

Sponsor-led academy schools are also brought in line with the MAT’s ‘vision’ for improvement. Often, there is focus on the cultural capital (or ‘lack thereof’) of the pupils, parents, place and space of the school. Kirsty Morrin (2022) argues that “Cultural interventions-as-academy-visions are sold as necessary but have often been dreamed up in an ill-defined and unevidenced past cultural ‘deficit’ in places and people.” (p.1).

Academies’ ‘visions’ in areas with higher levels of socio-economic disadvantage often focus on ‘improving behaviour’ and ‘raising aspirations’ of pupils whilst perpetuating the myth of the meritocracy (Kulz, 2017). This focus on cultural intervention in academy sponsorship schools is problematic as it is based on the deficit assumptions of people and places which serves to (re)produce raced and classed injustices (Kulz, 2017).

So, what does this mean?

There is a risk that academy trusts exacerbate schooling injustices in Bristol and across England. The academies programme is one system of the unjust present which does not need to exist in a just future. Kirsty Morrin (2022) suggests abolishing academies not just by reforming them, but by fundamentally questioning and rethinking the very basis of their existence and purpose, as well as that of the broader education system. This involves asking the critical questions: What are schools? Why do they exist? How do they function? And who do they serve?

References

BBC Panorama (2018) Profits before Pupils? [Video]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com (Accessed: 13 August 2024).

Department for Education (2023) What are academy schools and what is forced academisation? [Online]. Available at: https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2023/05/02/what-are-academy-schools-and-what-is-forced-academisation/ (Accessed: 13 August 2024).

Department for Education (2022) Transfer of land by local authorities – Schools Bill. [Online]. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1074509/Transfer_of_land_by_local_authorities_-_Schools_Bill.pdf (Accessed: 13 August 2024).

Dewes, I. (2024) Neoliberal Crises and the Academisation of the English School System: Why Governing Boards Choose to Join Multi-Academy Trusts. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Education Policy Institute (2017) The impact of academies on educational outcomes [Online] https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/impact-academies-educational-outcomes/

Kulz, C. (2017) Factories for learning: Making race, class and inequality in the neoliberal academy. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Morrin, K. (2020) ‘For the Abolition of Academies (and other connected institutions)’, The Sociological Review Magazine, 21 August. doi: 10.51428/tsr.kqlf1104.

National Education Union (2023) How school becomes an academy. [Online]. Available at: https://neu.org.uk/advice/your-rights-work/academisation/how-school-becomes-academy (Accessed: 13 August 2024).

Schools Week (2024) Highest-earning academy chiefs’ annual pay nears £500k. [Online]. Available at: https://schoolsweek.co.uk/highest-earning-academy-chiefs-annual-pay-nears-500k/ (Accessed: 13 August 2024).

Steeds, M. and Ball, R. (2020) From Wulfstan to Colston: severing the sinews of slavery in Bristol. Bristol: Bristol Radical History Group.

TES Magazine (2023) Ofsted: Local authority schools perform better than trusts. [Online]. Available at: https://www.tes.com/magazine/news/general/ofsted-local-authority-schools-perform-better-trusts (Accessed: 13 August 2024).

TES Magazine (2017) Academisation really privatisation by another name? Evidence suggests it might be. [Online]. Available at: https://www.tes.com/magazine/archive/academisation-really-privatisation-another-name-evidence-suggests-it-might-be (Accessed: 13 August 2024).

UK Parliament, Education Committee (2024) Ofsted and Government must rebuild trust and make major changes to school inspections. [Online]. Available at: https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/203/education-committee/news/ (Accessed: 13 August 2024).

Guest contributions to the Repair-Ed blog represent the perspectives of the authors.