School is a place I carry: Exploring the significance of embodied research approaches

Why is it important to consider the body in our research on the Repair-Ed project?

Our research understands the body as the site and context through which we experience and navigate the world. Afterall, schooling is not just something that happens to us. We are not just in the classroom, playground or at the school gate. Rather, we experience and engage with these places, and the people and things we encounter, through our bodies – our senses, sensations, emotions and feelings. We are interested in how these different dimensions of experience – place, objects, bodies, feelings and visceral sensations – intertwine to form what we might think of as our ‘embodied’ memories of schooling.

If we ask you to close your eyes and think back to your experience of school, it’s quite likely you will recall sensory bodily memories. Indeed, our research walking with former school pupils through their old school neighbourhoods has underscored the significance of the body moving through familiar places, in surfacing fragmented everyday memories of schooling.

This could encompass the smell of school dinners travelling through the echoey corridors, smudgy ink on fingertips, or the chorus of singing in school assemblies. It could also encompass felt memories of injustices experienced within and beyond the school gates. This is because racialisation and racism, and indeed classism, homophobia, transphobia, sexism, ableism and other – isms, are lived and felt in everyday encounters through the body.

In their book, Race and the Senses: The felt politics of racial embodiment (2020), Sekimoto and Brown highlight how race and racism are not only seen but are also “felt and sensed into being” in a multisensory way through the body. The visual dimension of race, which is often the focus of research, operates as a “visual economy of difference” that structures a hierarchical social order. Following Sekimoto and Brown, alongside this, our research also considers how hierarchical social orders become materialised and habituated through our bodies in everyday experiences of schooling. We understand the body as an important site of knowledge for understanding everyday lived experiences schooling, including of oppression, resistance and refusal.

This brings us to a crucial question: If we recognise racialisation, racism and classism as perceived, felt and registered through our bodies, how to do we consider this in our research approach? What do ‘embodied methods’ offer? And, crucially, how do we ensure we do not reproduce harm and trauma in our approach to researching with former pupils?

How can body mapping help us explore experiences of schooling across the city?

Embodied methods begin from a recognition that our memories and histories of schooling, and how they shape our present-day lives and futures, are a valuable form of knowledge. While there is a tendency for researchers to privilege forms of knowledge rooted in the mind and disregard ways of knowing centred in the body, we break from this through our care-full engagement (Manchester and Willatt, 2024) with embodied methods, such as body mapping.

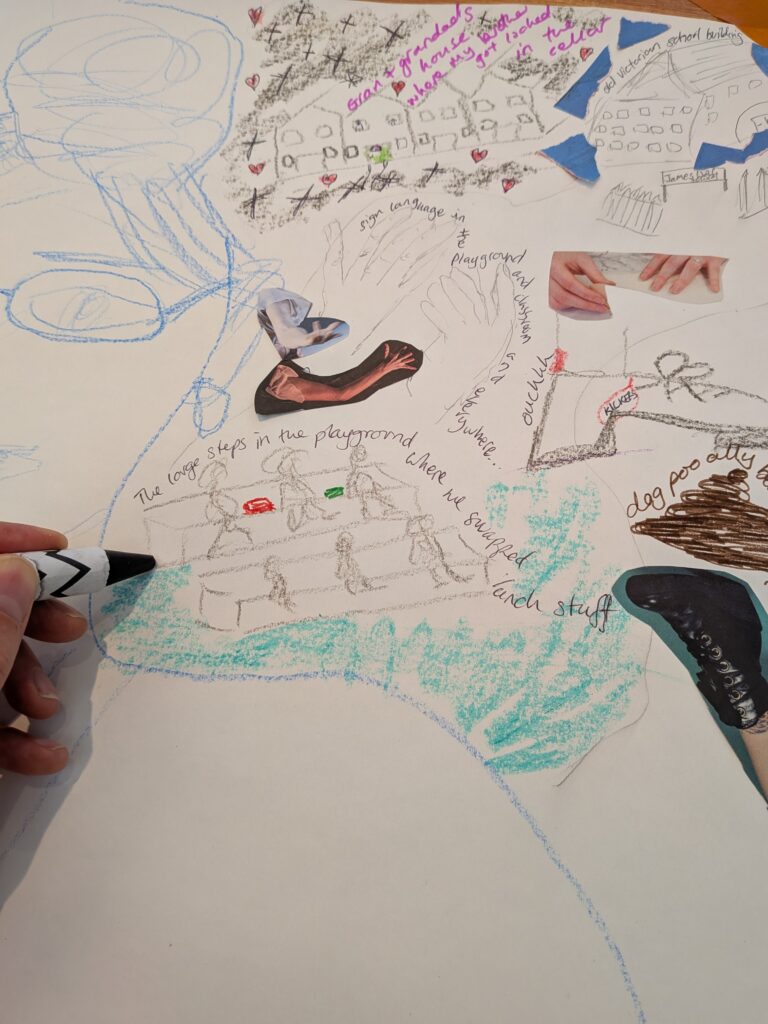

Body mapping is a process that invites participants to engage with their history of schooling, not as distant observers, but as active storytellers, drawing on their body memories (Barnes et.al, 2004; Gunn, 2017). By tracing the outline of their bodies and adding images, words and textures, participants explore how school was lived and felt, emotionally, physically and socially.

Over multiple workshop sessions, our body mapping approach aims to create space for participants to reclaim and reframe their everyday experiences of school, especially those experiences that are often left out of official histories. It opens a process for exploring memories of schooling, regardless of where or when that schooling took place.

We recognise that educational memory in Bristol is global, mobile and intergenerational: people may have been educated elsewhere, but shape the city’s schooling today as neighbours, carers, educators and community members. This approach honours the embodied memory of schooling as something that moves with people, lives in place and continues to affect how education is experienced today.

How might we conceive of body mapping as a practice of repair?

Drawing attention to our bodies through ‘mapping’ by engaging with our intimate understanding of what our bodies do, how they feel, and how they make sense of the world around them can be seen as an act of repair. This practice not only involves placing the body within a specific context but also contextualising it within a broader framework of social, political, and historical influences. By doing so, we bring awareness to the ways in which systemic structures shape our physical and emotional experiences.

Body mapping allows us to store and make sense of these experiences, highlighting how the body is not only a vessel for personal sensation but also a site where collective, structural forces are inscribed. It makes visible the intricate relationship between the individual and the collective, as well as the personal and the structural.

How does body mapping form part of our living archive approach?

Stories, learning, memories and maps shared in the body mapping workshops will become part of the People’s History of Schooling. This is an interactive map of shared stories of schooling in Bristol – past, present and future. It takes the shape of a living archive (Hall, 2001), a shared space where personal stories, gestures and feelings can be recorded, remembered and shared. The People’s History of schooling values the ordinary and emotional parts of life, explored through the body mapping process, and allows participants to share and contest their memories. It keeps the past alive by connecting it to the present, through dialogue, movement and acts of remembering.

What next?

We believe it is not fair to ask people to participate in methods that we ourselves haven’t experimented with. We recently got together as a team in the beautiful Art Room at Wellspring Settlement to follow our body mapping workshop process, develop our own body maps, and discuss ethical issues and challenges that might arise. We look forward to sharing a brief summary of the learning from our team workshop in a follow up blog post – watch this space!

References

Barnes, L.G., Podpadec, T., Jones, V., Vafadari, J., Pawson, C., Whitehouse, S. and Richards, M., 2024. ‘Where do you feel it most?’ Using body mapping to explore the lived experiences of racism with 10‐and 11‐year‐olds. British Educational Research Journal, 50(3), pp.1556-1575.

Gunn, S., 2017. Body mapping for advocacy. A Toolkit. Global initiative for justice, truth+ reconciliation. Body Mapping for Advocacy: A Toolkit. https://www.sitesofconscience.org/member_resources/body-mapping-for-advocacy-a-toolkit/

Hall, S., 2001. Constituting an archive. Third text, 15(54), pp.89-92.

Manchester, H. and Willatt, A., 2024. Towards care-full co-design with older adults: A feminist posthuman praxis. Journal of Aging Studies, 70, p.101250.

Sekimoto, Sachi, and Christopher Brown 2020. Race and the Senses: The Felt Politics of Racial Embodiment, Taylor & Francis Group