How young refugees and their families encountered England’s education system

Dr Jáfia Naftali Câmara, a Senior Research Associate at the University of Bristol, School of Education, reflects on her Bristol-based research with young refugees, examining how the co-creation of a zine can serve as an ethical, sustainable method for community-engaged research.

6th November 2025

Please read the full zine (comic) here:

You can also download a printable copy here: Refugee Stories, Education: Obstacles and Aspiration

Introduction

Scientific research has an extractivist nature historically intertwined with European colonialism and imperialism (Tuhiwai Smith, 2021). Its modus operandi has long been the creation of asymmetrical power relationships, where researchers, acting much like colonisers, take knowledge and information from participants to benefit their own careers and institutions. The resulting policy reports can further objectify the very people who shared their knowledge for that research (Abu Moghli, 2023). This critique is not intended to undermine the social benefits of research nor to romanticise ‘collaborative’ methods. Rather, it is an invitation to reflect on instances where our work may cause more harm than good. As an early-career researcher, I will explore how I navigated these contradictions during my doctoral studies.

My PhD focused on how young refugees and their families encountered England’s education system. During my doctoral education I felt that the training I received did not adequately prepare for the ethical dilemmas I encountered during my research in an area filled with ethical challenges. Since 2015, the peak of the so-called ‘refugee crisis’, public discourse has often subjected refugees and asylum-seekers to negative media and policy rhetoric. Within such a context, research risks further objectifying an already over-researched population by apolitically reproducing harmful stereotypes.

Consequently, I adopted the position that research is neither neutral nor apolitical. As a Global South migrant conducting social science research in a Global North context, I made decisions to try to shift power imbalances inherent in traditional research by engaging participants collaboratively and centring their power over their narratives.

This approach led me to critical and anti-exploitative research practices, prompting questions such as: What does ethical research entail beyond institutional procedures? How can research participation offer reciprocity and benefit? I understood that engaging participants in making decisions about the research could provide an answer. To counter the anti-refugee vitriol and make refugee perspectives accessible beyond academia, the young people and their families could participate in making decisions on research dissemination. I learned that research communication, publications and recommendations are important ethical sites, where researchers traditionally dominate, often leaving participants behind after their data is gathered.

Relational Ethics and Collaboration

Relational ethics can contribute to more equitable and reciprocal research collaboration by centring participants’ perspectives about the research itself. I found that my university’s procedural ethics clearance was insufficient for the ethical complexities I faced during my PhD. Since my methodology incorporated drawing and photography to make the research more engaging for the young participants, I extended this participatory approach to how we would communicate the findings.

Building and maintaining trust with participants was essential in mitigating power imbalances and maintain a relational approach. For example, I acknowledged that the PhD would directly benefit me academically, while I could not guarantee the same in return for their valuable time, stories and perspectives. However, I proposed that we could collaboratively decide what about their experiences and perspectives to share and how to communicate it to a wider audience.

How to communicate research findings in a way that the young people could more actively engage in and take ownership of the process?

As we engaged in discussions to decide how and if we could proceed, I asked them for their ideas. We brainstormed and eventually decided that creating a comic or an animation film would be visually appealing and an accessible way to share their stories. It then became my duty to secure funding for our collaborative project.

I was successful in obtaining a £6000 award from the University of Bristol. The proposal centred on combining ethnographic research and the arts to engage young refugees and their families in knowledge production and research dissemination. We chose to create a zine (comic) over an animation, as it was more financially feasible. This allowed me to prioritise paying an honorarium to each young participant for their time and creative contribution.

While some might question sharing funding with participants from a traditional, “objective” research point of view, I argue that it was a necessary ethical decision. Co-creating the zine required time and dialogue between the researcher, participants and two illustrators. For young people and families living in precarious financial conditions, time is a valuable resource. I understood that it would have been more unethical not to take practical measures to mitigate any potentially exploitative practices.

Co-creating Content for the Zine

We collaborated with two illustrators (Arc Studio) to create a zine that reflected how the young people and their mothers wanted to be portrayed. The participants led the creative process, starting with sketching their self-portraits to guide the artists. For example, Temesghen paid attention to how his hair would be portrayed, asserting ownership over his image (Figure 1).

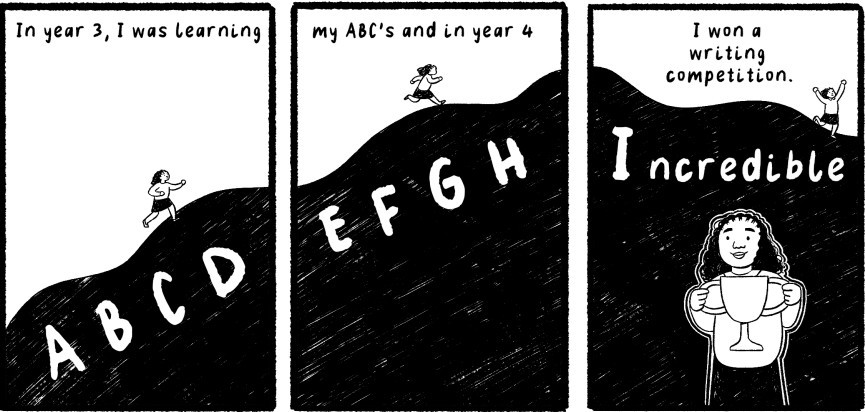

The participants made decisions on how the comic would be organised and selected which of their stories to include, and the narrative tone. Olivia Sarah chose to highlight a story of academic success (Figure 2). She wanted to share how she won a writing competition in Year 4, just a year after learning her ABCs while her peers were “ahead” learning more complex subjects.

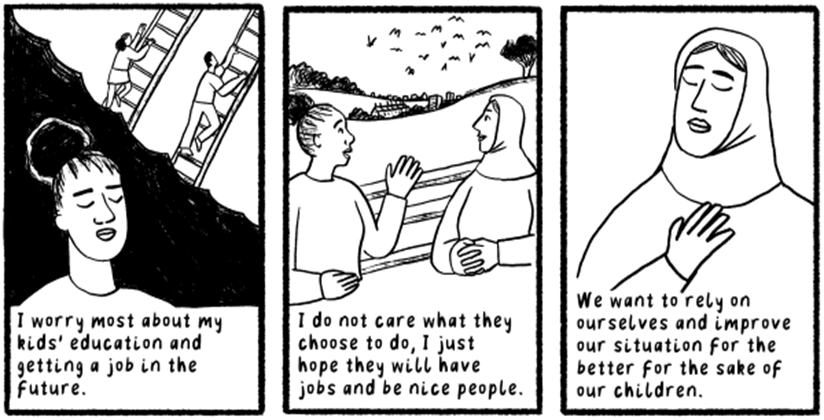

Olivia wanted to share this story to encourage other refugee children that they could also overcome the initial barriers of learning in a new language and living in a new country. Similarly, the mothers, like Rivkah and Fatima, contributed reflections on their concerns and hopes for the future (Figure 3).

The comic, Refugee Stories: Education: Obstacles and Aspirations, was a direct manifestation of my ethical commitments. It provided an accessible platform for first-person narratives and aimed at countering the dominant negative media and policy discourses about refugees.

Conclusion

This project taught me that power imbalances in research are inherent. However, as a doctoral researcher, I learned that there were ways to actively mitigate extractive practices in social science research by

- Building sustained relationships based on trust (confiança), avoiding parachute and parasitic science and knowledge production. Trust can be nurtured by listening to participants, setting realistic expectations about the research and communicating its limitations.

- Collaborating with participants not merely on data collection but on research goals, methodology and dissemination.

The co-created zine is a testament to the importance of more actively engaging participants in the research process. Although participants may not always have the availability or desire to deeply engage, creating the opportunity for collaboration can help transform the ethical paradigm of research.

Discussion Questions

- How have you navigated similar ethical challenges in your work, and how could doctoral training (and institutional practices) be improved to better prepare researchers for these complexities?

- How might you use the content shared in the zine, Refugee Stories, for teaching and learning?

References

Abu Moghli, M. (2023). Research ethics in the occupied west bank and the gaza strip: Between institutionalisation and the power of praxis, globalisation. Societies and Education, 21(5), 677–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2023.2165479

Câmara, J. N. (2025) ‘Relational ethics of care in research with young people: reflections from a study with young refugees and their families’, Cambridge Journal of Education, 55(2), pp. 159–188. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2025.2469849.

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2021). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (Third ed.). Bloomsbury Academic.

Guest contributions to the Repair-Ed blog represent the perspectives of the authors.